WRITTEN BY: AURORA SIMIONESCU

In November 1967, Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish discovered a rather peculiar source on the sky, which was sending a radio signal once every 1.33 seconds, with remarkable regularity. For a while, the source was affectionately nicknamed LGM-1, short for “little green men” – until it was realized that an astrophysical source known as a pulsar was responsible for this kind of signal.

A pulsar is a very compact, tightly packed ball of neutrons, also known as a neutron star, which can form from the dense inner core of a massive star after the rest of it explodes as a supernova. Not all supernova explosions leave a pulsar behind. Pulsars are special because they emit a beam of very energetic particles from their magnetic poles and, as they rotate, this beam sweeps through the cosmos, kind of like an astronomical lighthouse. For some pulsars, the beam will periodically point towards Earth. The time elapsed between signals differs from pulsar to pulsar. It can be as short as 1/1000 of a second, and repeats at intervals that can be more precise than an atomic clock.

So, somewhat disappointingly perhaps, the periodic radio signals discovered in 1967 turned out not to be coming from little green men after all. But, with stars producing the chemical elements necessary for the existence of life everywhere in the Universe, and with so many billions of stars just in our own Galaxy, and so many billions of galaxies in the cosmos, isn’t it overwhelmingly likely that there is somebody else out there? As Carl Sagan put it, otherwise, the Universe would seem like an awful waste of space.

Astronomer Frank Drake famously came up with an equation to describe the probability of finding life on another planet in the Milky Way. Drake asked: how many stars are there in our Galaxy? Of these, how many stars have planets, and how many planets does one star typically host? Of these planets, how many planets have a rocky, solid surface? How many of them are in a “habitable zone”, not too close to the star so all water would evaporate, and not too far so that it would freeze? Of the rocky planets where the temperatures allow liquid water to exist, on how many does simple life, such as bacteria, evolve? Of the planets where bacteria evolve, on how many does life become more complex? On how many does intelligence develop? How many intelligent civilizations develop the ability to communicate, for example by sending radio signals? And, finally, what is the typical lifetime of such a civilization, before it gets destroyed by natural or self-made calamities – which is to say, what is the chance that such an alien civilization, if it ever existed, is still alive today?

All of these questions are interesting. Some belong more to the fields of biology, psychology, or philosophy; but astrophysicists are recently making great progress toward answering the first few of Drake’s points. There are an estimated 300 billion stars in the Milky Way, and many of these have planets. The first planet ever discovered was actually revolving around a pulsar, and the way scientists figured out the planet was there was because it was affecting the time intervals between the radio signals received from the pulsar. Since then, many methods have been used to search for planets around other stars.

Some of these methods involve Newton’s third law: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The planet pulls on the star it is revolving around, just as much as the star pulls on the planet, keeping it in orbit. The star is generally pretty big, so the pull from the planet doesn’t move it too much, but it does make it move ever so slightly, and these motions can be measured – as a change in either the position or especially the velocity of the star. The bigger the planet, and the closer it is to the star, the more the star moves and the easier these motions can be detected. So, in the early years of exoplanet searches, astronomers came up with lots of weirdos: planets bigger than Jupiter located as close to their star as Mercury is to our Sun.

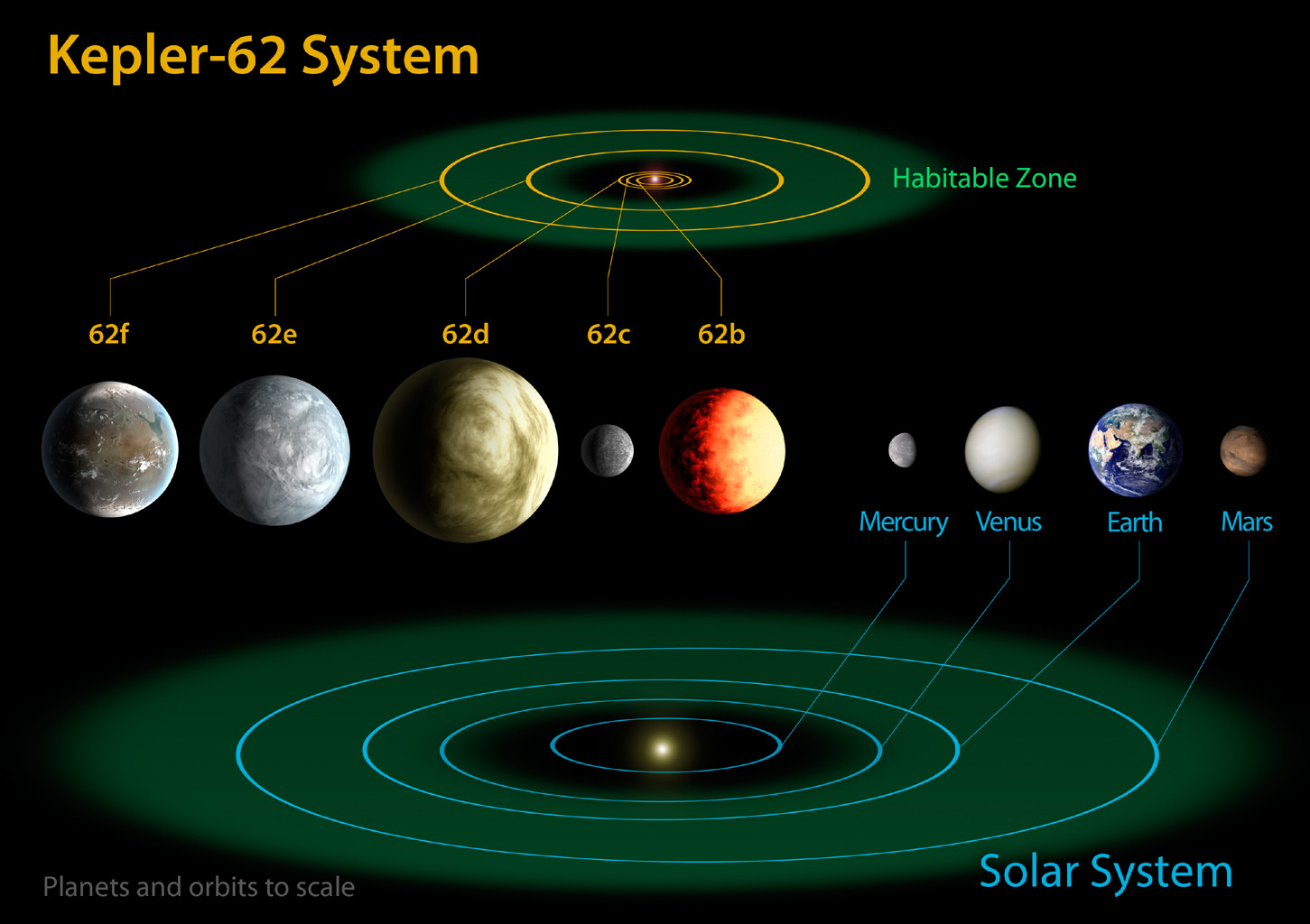

This had people wonder, for a while, if our Solar system was somehow special. But, recently, NASA’s Kepler mission performed a much more sensitive search for planets, using the so-called “eclipsing” technique. Kepler was a space telescope which monitored the brightness of 150,000 stars in our Galaxy for several years. When a planet passes in front of the star, every now and then it shades a small fraction of the star’s surface from our view, and the brightness of the star appears to decrease for a short time. Kepler was looking for planets in this way, and found many planets which were similar in size to the Earth.

Kepler-62 and the Solar System Image credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech

According to the latest estimates, Kepler found that at least one out of every six stars hosts an Earth-sized planet. About one third of the planets discovered by Kepler within the first year were in multiple-planet systems, with two or more planets around the same star. There are at least as many planets as there are stars in our Galaxy. Although most of the planets discovered with Kepler are still too close to their stars to have liquid water, there are some notable examples of other worlds that are quite similar to our own. A system of 5 planets was detected around the star Kepler-62. Two out of the five planets are in the habitable zone, where water can exist in liquid form. One of these planets is only 40%, and the other one 60% bigger than our Earth. Kepler-69, which is a sun-like star, was also found to host two planets, one which is only 70% larger than the size of Earth, and orbits in the habitable zone with a period of 242 days, resembling that of our neighboring planet Venus.

It seems then that Earth has many siblings in our Galaxy where the conditions are right for life to develop, so it’s very probable to find simple life like bacteria in other corners of the Milky Way. As for more complex life forms, it’s very difficult to tell. We have a hard time identifying the intelligence of many life forms right here on Earth, so the question of extraterrestrial intelligence may have to wait until we have learned to communicate with whales, elephants, octopi, parrots, dolphins, pigs, and chimpanzees, which are thought to be some of the smartest animal species on our planet.